January 5, 2026

Herman the Cat, Expert Mouser

How a young gray cat received official Coast Guard credentials and kept Baltimore’s wartime docks running during World War II.

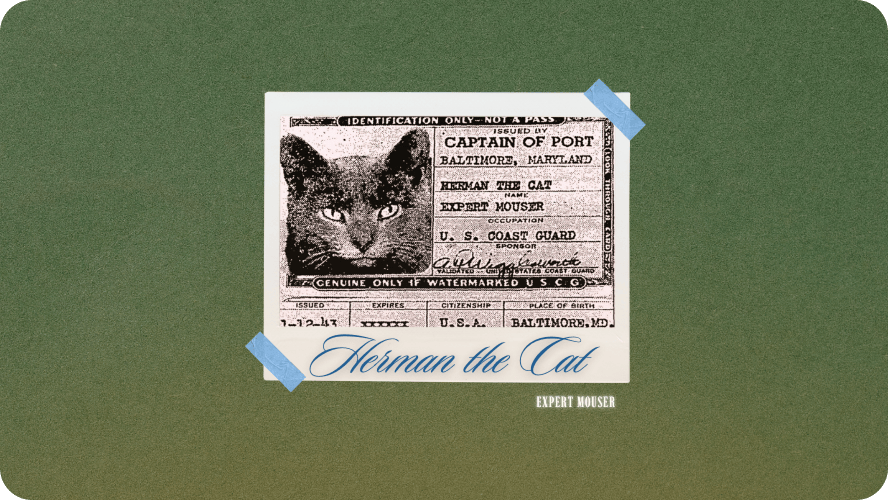

In January 1943, at the height of World War II, the U.S. Coast Guard issued an official photo identification card to a cat in Baltimore.

His name was Herman. His occupation was listed as “Expert Mouser.” He had a serial number, a physical description, and a fingerprint. Or rather, a pawprint.

With that card, Herman became an authorized Coast Guard worker, free to roam the docks of Baltimore’s busy harbor while the country prepared ships, supplies, and crews for the war overseas.

Wartime ports had a serious problem. Rats thrived along the docks, slipping between cargo holds and warehouses, chewing through ropes, stealing food, and spreading disease. In an era before modern pest control, they were more than a nuisance. They were a threat.

As one Army doctor told The Baltimore Sun in 1943, “It is a good thing to get rid of rats in general. They carry endemic typhus.” The solution, in many cases, was simple and centuries old.

Cats.

Herman was just 8 months old when he was officially hired. Regulations did not say anything about cats being forbidden from service, and so, in a move that feels both practical and absurd, the Coast Guard issued him credentials. His identification card listed his height, weight, green eyes, and gray coat. Where a human fingerprint would normally appear, Herman left a neat pawprint.

Bureaucracy had found a loophole, and Herman walked right through it.

With his ID, Herman had unrestricted access to Pier 4 on Pratt Street. Dock workers were not allowed to stop him as he moved through restricted areas, climbed over crates, and carried out his work. His induction was even featured in Paramount newsreels, shown in movie theaters around the country. Not every dock worker received that kind of national attention.

But Herman’s job extended beyond rat control. Morale mattered during the war, and Herman provided it freely. He allowed dock workers and sailors alike to pet him, an act of trust that suggested he understood his role went beyond pest management. A chief boatswain described him as “an ambassador of good will. A diplomat.”

Herman belonged to a much older maritime tradition. For centuries, cats sailed with crews to control vermin, bring luck, and keep sailors company. Even after the Navy banned alcohol aboard ships, cats remained welcome during World War II, valued for their usefulness and their calming presence in dangerous, high-stress environments.

What happened to Herman after the war is less clearly documented. Records focus on his service rather than his retirement. What is known is that he worked the Baltimore docks during one of the most intense periods of global conflict, at a time when animals were still considered useful, trusted, and officially welcomed into daily operations.

That window did not last.

As decades passed, policies tightened. Quarantine laws grew stricter. Risk assessments multiplied. Animals gradually disappeared from docks, ships, and government workplaces.

Herman remains a snapshot of a moment that no longer exists. A time before paperwork closed every gap, when necessity and trust occasionally outweighed regulation, and when a small gray cat could earn a government ID and help win a war.

Before rules came first, sometimes animals were simply allowed to help.

More stories

Furrend circle

Be the first one to hear about updates