February 4, 2026

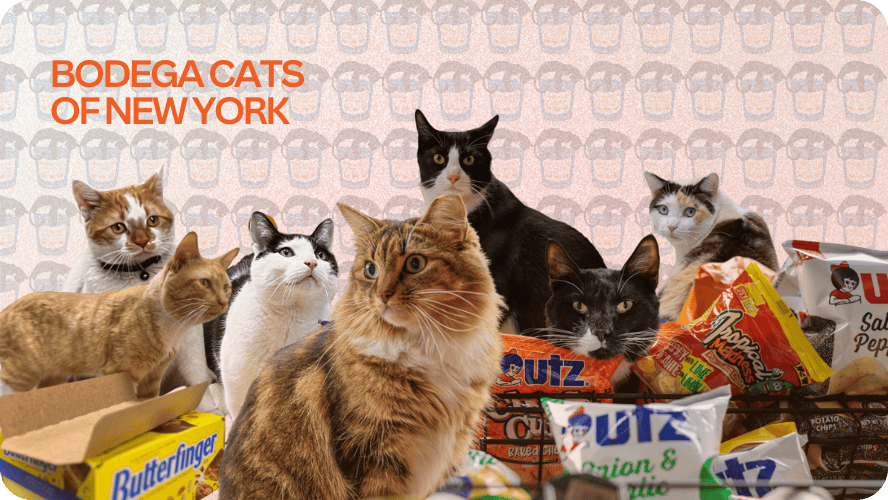

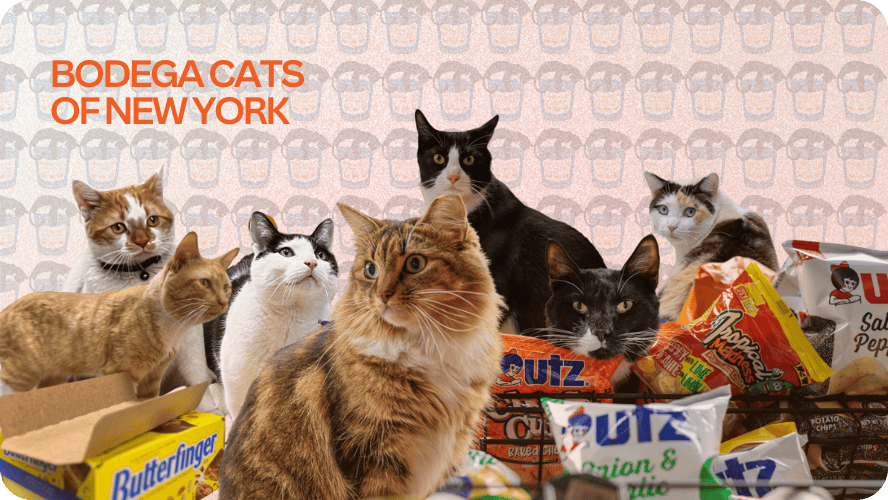

Bodega Cats of New York

Daniel Rimada on documenting New York’s working cats, the people behind them, a long history we tend to forget, and his upcoming book.

New York’s corner stores are more than places to grab a coffee, a BEC sandwich, or a last-minute charger. They’re often open when everything else feels closed. Owners know their regulars. Regulars know which fridge hums too loudly.

Where there’s food, there are mice. And for generations, the solution was simple: you hired a cat.

Over time, those cats picked up a name of their own. Bodega cats. They nap between bags of chips, patrol freezer aisles, and occasionally judge customers from the counter. They’ve become familiar figures, photographed, shared, and recognized far beyond the neighborhoods they belong to.

But behind every cat curled up by a register is a longer story. One that includes immigration, labor, neighborhood trust, health inspections, and an "agreement" between humans and animals that has existed for centuries.

Daniel Rimada has spent years documenting these cats not as internet curiosities, but as workers and cultural fixtures holding together small shops and the communities around them. What began as casual photography in Fort Greene grew into a serious archival project, real-world advocacy, and eventually legislation that put shop cats on New York City’s agenda for the first time.

We spoke with Daniel about how the work began, why framing matters, the long history of working cats, the bill that changed the conversation, and his upcoming book, Bodega Cats of New York.

Do you remember the moment when bodega cats shifted for you from being “a charming New York thing” to something worth documenting seriously?

It wasn't a single moment. I started taking photos in Fort Greene just because I liked the cats and the neighbors who kept them. The shift happened when I started talking to store owners. They'd tell me about rat problems, health inspectors, and customers complaining about allergies. One guy told me he'd had the same cat for eleven years and still worried about getting fined. After that, I couldn't really go back to just taking cute photos.

Why does the worker framing matter, and what gets lost when these animals are treated purely as content?

Because there's a person behind every one of these cats. Usually, an immigrant shop owner who's had the cat for years and depends on it. When you flatten that into "cute cat in a store," you lose the guy who still worries about getting shut down. The framing matters because accuracy matters.

” There’s a person behind every one of these cats.

Do you see your work as part of the longer lineage of working cats?

Yeah. Ship cats, distillery cats, library cats, government mousers. It's all the same thing. Humans and cats are figuring out a deal that works for both. Bodega cats are just the New York version. I think that context matters because it pushes back against the idea that this is some quirky internet thing. It's ancient.

Was legislative recognition always part of the vision?

No. Honestly, the documentation came first and I didn't have a bigger plan. But I kept hearing the same stories. Health code enforcement, threats of fines. So we started a petition, got over 13,000 signatures, and that eventually became City Council legislation, Intro 1471. The advocacy part just emerged because the documentation revealed a problem.

What drew you to the book format?

A book is permanent. Social media rewards novelty over depth, and I wanted something that could hold the full scope. The cats, the store owners, the neighborhoods. The photography is by Gulce Kilkis, and her work captures those relationships in a way that just doesn't land the same on a feed. The book comes out October 2026 through Quarto. I'm excited for people to see these cats in context. Not as one-off images.

What feels most energizing right now outside the book?

I also own a historical walking tour about cats in New York, going back to the 1800s. Different angle than the bodega work, but same underlying question. What roles have cats played in this city, and why have we forgotten most of them?

How did Cocoa and Charles come into your life?

They're Ragamuffins, both seven. Got them as a pair when they were kittens from a Facebook post, just shy of Covid. Companion cats. They've never worked a day in their lives, and they're not about to start. I think that distinction is useful, actually. Not every cat is a working cat. Cocoa and Charles just remind me that not everything has to be transactional.

Our thanks to Daniel for taking the time to share his work and perspective. You can learn more about his upcoming book, Bodega Cats of New York, on his website, and follow his ongoing documentation of New York’s working cats on Instagram.

More stories

Furrend circle

Be the first one to hear about updates